My father, Donald G. Gillin, died a year ago tonight. His death from Alzheimer’s Disease at 75 was tragic for one so intellectually vibrant, but Alzheimer’s is an unforgiving disease. He had taken great care of his body for many years, but he was unable to escape the clutches of an illness that robbed him of his mind.

My father, Donald G. Gillin, died a year ago tonight. His death from Alzheimer’s Disease at 75 was tragic for one so intellectually vibrant, but Alzheimer’s is an unforgiving disease. He had taken great care of his body for many years, but he was unable to escape the clutches of an illness that robbed him of his mind.

I’m posting this entry because I recently became aware that news of his death apparently did not disseminate through the standard communications channels. My dad was a terrible record keeper. He had no Rolodex and whatever contact information he had consisted of phone numbers scrawled on slips of paper that he kept in his wallet. When he died, I had no way to contact the people who might want to know the news. I submitted obituaries to his alma mater and to the leading professional journal in his field of Asian studies, but apparently neither ever published anything. I learned this by contacting a colleague and friend of his recently, who was unaware of my dad’s passing.

I’m posting this in hopes that someone searching for news about my dad will come by this blog entry. Below is the obituary that ran in the local newspaper. Please contact me if you’d like to know more.

SHREWSBURY, MA. – Donald Gillin, Ph. D., a noted China scholar and former head of the Asian Studies program at Vassar College, died on Aug. 28 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. He was 75.

Dr. Gillin taught at Vassar from 1968 until his retirement in 1992. He was previously a faculty member at Duke University. A fluent Mandarin-Chinese speaker, he was noted for his talents as a lecturer and storyteller. His innovative “Hollywood on Asia” course at Vassar at one point drew enrollment of almost 15% of the Vassar student body. An accompanying slide set on images of China in popular media sold more than 700 copies when produced by The Asia Society.

Dr. Gillin served as a visiting member of the faculty at the Universities of Michigan and North Carolina, Stanford University, San Francisco State College, Arizona State University and Sir George Williams University in Montreal. He delivered scores of papers and lectures at conferences and symposia around the world, including many meetings of the Association for Asian Studies.

His books included Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911-1949 (Princeton University Press, 1967) and East Asia: A Bibliography for Undergraduate Libraries (BroDard Publishing Company, 1970). Warlord is still in use as a college textbook nearly 40 years after it was published. He co-authored Last Chance in Manchuria (Hoover Press, 1989) and Prescriptions for Saving China: Selected Writings of Sun Yat-sen (Hoover Institution Press, 1994). His monograph, Falsifying China’s History: The Case of Sterling Seagrave’s The Soong Dynasty ( Hoover Institution, Stanford University, 1986) caused a small sensation in Asian studies circles for its impassioned refutation of the bestselling Soong Dynasty.

Dr. Gillin also published dozens of articles in scholarly journals, including The Journal of Asian Studies, South Atlantic Quarterly, Encyclopedia Britannica, Journal of Modern History, and American Historical Review. Born in San Francisco, Dr. Gillin earned B.A., M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Stanford University. A recipient of Ford Foundation and Stanford grants, he studied Chinese language in Taiwan and Hong Kong before joining the Duke faculty in 1959. He joined the Vassar faculty in 1968.

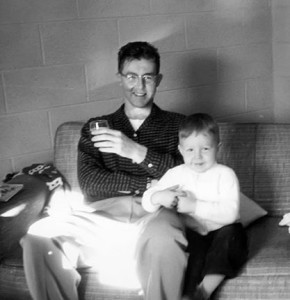

Dr. Gillin’s wife, Rose Marie, died in 2000. He leaves two children: Paul Gillin of Westboro, Mass. and Presto Rubel of Brimfield, Mass. He also leaves two grandchildren. A cremation is planned. Donations may be made to the Alzheimer’s Association. Communications may be sent to Paul Gillin, 1 Garfield Dr., Westborough, MA 01581.

Addendum, July 2014

My dad was a brilliant but quirky man. In addition to modern Chinese military history, he was an expert on the Civil War and very proficient in the history of both world wars. He spoke Chinese so fluently that he sometimes fooled native Chinese speakers on phone calls.

He had an unbelievable mind for facts and trivia. As a kid, I liked to watch the game show Jeopardy! My dad hated game shows, so whenever he caught me watching one he’d scold me for wasting my time with such rubbish. Then he’d start answering the questions, often running the board before leaving in disgust. I used to tell him that if he could get over his aversion to game shows he could have won us $100,000 on Jeopardy.

As brilliant as he was, he struggled to distinguish between right and left until his dying day. He once lost his wallet at the Poughkeepsie train station because he took it out of his pocket to look up his own phone number and left it in the phone booth. When he died I went through his wallet, a grotesque blob of leather stuffed with hundreds of pieces of paper, nearly all of them phone numbers. I found my own number at least a dozen times, covering three houses and more than 15 years. His own number was in there several times as well. My dad couldn’t be bothered with keeping detailed records. His mind contained most of what he needed to get through life.

The tiniest mechanical tasks could send him into a rage. He had absolutely no mechanical skills – couldn’t even operate a screwdriver. It wasn’t for lack of motor skills, though. He played a mean game of tennis, despite having never had a lesson. His tennis form was terrible; he was all wrist and he served with an odd scooping motion. He was surprisingly devastating, though. He played with manic intensity, often staying on the court for two hours in the brutal North Carolina summer heat. Then he might stroll to class. As one former student recently wrote me, “He would come in the early afternoon class fresh from the tennis court, his racket in his hand, and would tell us about Chinese peasants, or Yen Shi-shan, whose biography he was writing then.”

He was a brilliant lecturer and storyteller, but he hated meetings and largely avoided faculty get-togethers, preferring the company of a few close friends. He was basically a loner who nevertheless thrived in front of groups. He loved to tell stories but hated small talk.

Late in my dad’s career, he figured out a way to combine his love of Hollywood films with his passion for China. Understand that his love of movies was far more than just a pastime. I believe he had seen just about every major motion picture that had come out of Hollywood between 1945 and 1960, and he filed them away in his prodigious memory. As a teenager, I used to play a game with him by picking movie titles at random from TV Guide. He would respond with the year the film was made, the names of the lead actors, the director and a summary of the plot. As I recall, his accuracy rate was between 80% and 90%. It was awesome.

In the late 1970s, he hatched the idea of an undergraduate course called “Hollywood on Asia.” Each class consisted of a full-length popular film – usually a B&W Classic like “The Mask of Fu Manchu,” followed by a lecture. The course became a modest sensation at Vassar, where it enrolled as many as 250 students in one semester. That’s 15% of the student population. Many students no doubt thought it would be a gut course, but my dad took the topic seriously and he graded hard. I don’t remember specifics, but he said he gave out a lot of Cs and Ds on the term paper.

The course was controversial. While the students loved it, some of the faculty criticized my dad for dumbing down scholarship. He thought they were jealous, and they probably were. It didn’t help that he took things a bit too far with his next venture, which was a slide presentation on Chinese sexual imagery in popular culture. The images he used weren’t obscene, but some of them were pretty racy, and the reaction from his colleagues was largely negative. That presentation was probably one of the main reasons the Vassar administration forced him into early retirement at age 63. That coincided with the beginning of my mother’s long downward spiral from diabetes and Lupus, which ended in her death in May 2000. My dad’s Alzheimer’s symptoms became apparent about a year later.