Live-blogging from the IBM Watson University Symposium at Harvard Business School and MIT Sloan School of Management. Additional coverage is on the Smarter Planet Blog. .

Panel discussion: How Will Technology Affect Productivity and Employment?

Moderator: Erik Brynjolfsson – MIT Sloan, CDB

Panelists: David Autor – Economics, MIT; Irving Wladawsky-Berger, MIT, IBM Emeritus; Frank Levy, MIT

| The Next Big ThingThis is one in a series of posts that explore people and technologies that are enabling small companies to innovate. The series is underwritten by IBM Midsize Business, but the content is entirely my own. |

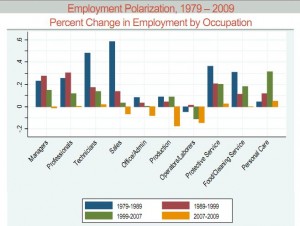

Autor: The idea that machines eliminate jobs is a fallacy. A century ago, 38% of the US population worked on farms. Today it’s 2%. But we don’t have 36% unemployment. We’re in a period where the scope of what can be done by machinery is expanding rapidly. If we look at 10 categories of occupation (shows a chart), there are three categories: Low-paid positions like food service work; mid-level, relatively low-paid positions like clerical jobs; and relatively highly paid jobs like professional, technical and managerial.

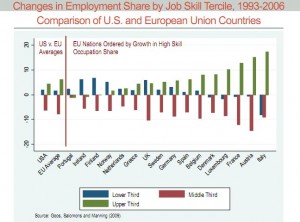

What we see is a decline in operative production jobs and clerical/administrative support jobs. The middle third are the jobs that are declining most quickly. Should we be worried about that? Probably, because it can lead to policies that are intended to preserve these positions instead of moving toward the jobs that are growing.

Wladawsky-Berger: About 80% of the job growth is in information-intensive service jobs. We’re living in a time of sustained high unemployment and this is concerning. Who will pick up the challenge of providing these jobs? People are looking to large businesses, but they are shedding these jobs along with everybody else. Others look to government, but in my experience government won’t do that.

The top-down approaches aren’t going to work, but neither do I want to tell people that they’re on their own and that they have to take a more entrepreneurial approach. The world is becoming more entrepreneurial.

Levy: Everything we see here is colored by the recession, but this recession doesn’t have much to do with computers, it has to do with housing bubbles. The mid-skill decline is very real. Development is very uneven. Natural language processing has improved a lot, machine vision hasn’t and technologies like judgment and practical sense really haven’t gone anywhere.

People look at the Google truck and say it’s remarkable that it’s gone 2,000 miles without an accident. What really happened was that Google made detailed maps of the infrastructure it would be traveling. Without that infrastructure, this car doesn’t have the driving ability of a 16-year-old who just got a permit. So while this technology is promising, the Teamsters shouldn’t be protesting yet.

Brynjolfsson: Is there a future for the people who have those kinds of jobs?

Wladawsky-Berger: It has to be more entrepreneurial than top-down. The kinds of jobs that MIT and Stanford graduates have don’t scale very well. Small businesses don’t tend to create many jobs.

Can we apply technologies that have traditionally been available only at the high end and make them easier to use? Can there be new retail services, trades, sustainability-oriented businesses where these skills can be applied?

Levy: I can give you an example of one of our graduates who is now running a business making high-end stationery. It’s a good living, but it’s a small piece of the market.

Autor: in a lot of countries there are businesses that we might call entrepreneurial but which are really people just getting by. Most people want to be employed. When the economy booms, people tend to stop working for themselves and go to work for other people. Asking people to create new jobs is asking a lot.

What are the advantages of humans? Common sense, judgment, physical flexibility, understanding. It’s solving novel problems. Positions like cleaning driving actually require those capabilities.

Wladawsky-Berger: Will global enterprises create these jobs? they’re becoming more distributed and moving a lot of tasks to the supply chain. A lot of people in the supply chain could be these mid-skilled people.

Autor: Cleaning restrooms requires a lot of flexibility, but it’s not entrepeneurial.

Brynjolfsson: So what skills should we be training people for?

Levy: One of the problems is you’re problem-solving by analogy. In the old world, where you were problem-solving by algorithm, it was pretty simple. Now you need to understand how things are similar and how you would use analogies to make decisions.

Autor: Germany has done a good job by training for needed skills and by reducing wages and increasing flexibility. It was painful, but when the shock hit, they were able to handle it better.

The US has a very good system for elite education. We don’t have a particularly good way to handle the people who can’t go to college. The traditional feeders like unions and apprenticeships aren’t as available today. The jobs that are emerging are those that require some level of post-high-school education. We have an incredibly big for-profit post-high-school education sector, but the only guarantee you have is that you’ll come out with a lot of debt. We’re squandering a lot of mid-level talent.

Levy: When you’re talking about a lack of training for people oer 30, you also have to look at where we are in training people under 18. That’s a problem in the pipeline.

Wladawsky-Berger: For these mid-skill jobs you need post-high-school education. I’m not saying a BA in English – in fact, that might be a bad idea – and I’ve been hoping that government agencies would decide that this is better than paying welfare and unemployment.

Autor: Health care will grow and there will be opportunities. If I were asked what people should study for, I’d say a health care worker. I don’t think we’re over-investing in college, I think we’re under-investing in other areas. The high school graduation rate is falling for males in the U.S. We ought to think carefully about how we would use that talent for a set of opportunities that’s appropriate. They need skills beyond the generic skills they find in high school. They need vocational education.

Levy: In the case of medical care, the whole issue of judgment is very important. When you’re talking about eliminating unnecessary procedures, there’s quite a bit of judgment involved. These are not problems that machines can address.

Autor: Look at an example of something that’s been automated out of value: Horses used to be our main form of locomotion but now they’re hardly needed. The difference between people and horses is that horses don’t accrue wealth from the internal combustion engine and we do. We’re getting wealthier collectively but not individually.

Audience question: I’m concerned with how we communicate these changes who aren’t economists so we can avoid reactions like what happened with stem cell research?

Wladawsky-Berger: The consensus of everything I’ve read is that when we transitioned from the agriculture to the industrial age, literacy went way up. High school became the ticket to the mid-skill, mid-pay class. In today’s world you need the next level of education: information-based literacy. You need to be comfortable working with information and you need social skills. This prepares you to be much more flexible in the new working environment. People who learn to use these tools can make a good living.

Audience question: It seems that our society fails people who need to change careers. Our unemployment system doesn’t encourage people to try new things for fear that they may lose benefits. Our education system also doesn’t foster skills training.

Autor: We have very little of what other countries call activation systems for people who have lost their jobs. We have a trade-adjustment system that does a terrible job. The problem is that the Republicans hate trade adjustment and blame everything on trade, and the unions hate re-skilling. So we have trade adjustment, which does very little.

Audience question: What about the possibility of trading off standard of living for other benefits, such as fewer work hours?

Autor: There’s a societal choice to trades off work for standards of living. You can work two days a week and make less money and some people might choose that. But we want to work less and have higher standards of living. We have more and more, but the rewards are concentrated in fewer hands. Having more rewards doesn’t solve the skill problem.

Wladawsky-Berger: I think we need more collaboration between the private and public sector. So the government does more to help people while they’re training for jobs, but the jobs are provided by the private sector.