From Innovations, a website published by Ziff-Davis Enterprise from mid-2006 to mid-2009. Reprinted by permission.

For more than 15 years, Ken Brill has preached the gospel of optimizing data center availability. Now he’s evangelizing a more urgent message: data centers must reduce their environmental footprint or risk letting their spiraling power demands run away with our energy future.

Brill’s Uptime Institute serves Fortune 100-sized companies with multiple data centers that represent the largest consumers of data processing capacity in the world. A typical member has 50,000 square feet of computer room space and consumes “a small city’s worth” of utility power. For these companies, uptime has historically been the brass ring; their need for 24 x 7 availability has trumped all other considerations. That has created a crisis that only these very large companies can address, Brill says.

Basically, these businesses have become power hogs. They already consume more than 3% of all power generated in the US, and their escalating data demands are driving that figure higher. A research report prepared by the Uptime Institute and McKinsey & Co. (registration required) found that about one third of all data centers are less than 50% utilized. Despite that fact, the installed base of data center servers is expected to grow 16% per year while energy consumption per server is growing at 9% per year.

“During the campaign, John McCain talked about building 45 nuclear power plants by 2030,” Brill says. “At current growth rates, that capacity will be entirely consumed by the need for new data centers alone.”

Potential for Abuse

That might not be so bad if the power was being well used, but Uptime Institute and its partners believe that data centers are some of the country’s worst power abusers. In part, that’s because uptime is no longer the key factor in data center performance, even though data center managers treat it that way. Data centers used to serve the needs of mission-critical operations like credit card processing. Response times and availability were crucial and companies would spend lavishly to ensure perfection.

Today, many data centers serve non-critical application needs like search or large social networks. Uptime isn’t a top priority for these tasks, and spending on redundancy and over-provisioning is a waste if the only impact on the user is a longer response time for a search result.

The move to server-based computing as a replacement for mainframes has actually increased data center inefficiency. Whereas mainframes historically ran at utilization rates of 50% or more, “Servers typically operate at less than 10% utilization,” Brill says, “and 20% to 30% of servers aren’t doing anything at all. We think servers are cheap, but the total cost of ownership is worse than mainframes.”

Wait a minute: not doing anything at all? According to Brill, large organizations have been lulled into believing that servers are so cheap that they have lost control of their use. New servers are provisioned indiscriminately for applications that later lose their value. These servers take up residence in the corner of a data center, where they may chunk away for years, quietly consuming power without actually delivering any value to the organization. In Brill’s experience, companies that conduct audits routinely find scores or hundreds of servers that can simply be shut off without any impact whatsoever on the company’s operations.

And what is the implication of leaving those servers on? Brill compares the power load of a standard rack-mounted server to stacking hairdryers in the same space and turning them all on at once. Not only is the power consumption astronomical, but there is a corresponding need to cool the intense heat generated by this equipment. That can consume nearly as much power as the servers themselves.

The strategies needed to combat all this waste aren’t complicated or expensive, he says. Beginning by auditing your IT operations and turning off servers you don’t need. Then consolidate existing servers to achieve utilization rates in the 50% range. He cites the example of one European company that merged more than 3,000 servers into 150, achieving a 90% savings in the process. “People think this is an expensive process, but it actually saves money,” he says.

In the longer term, making data center efficiency a corporate goal is crucial to managing the inevitable turnover that limits CIOs to short-term objectives. The commitment to environmental preservation and power efficiency needs to come from the top, he says.

Uptime Institute has white papers, podcasts and other resources that provide step-by-step guides to assessing and improving data center efficiency. This is a goal that every IT professional should be able to support.

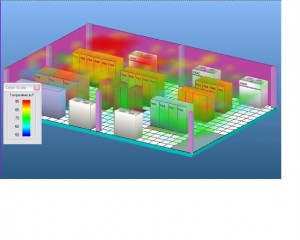

The graphic at right may look kind of cool, but it’s anything but. It’s actually a simulation of the heat distribution of a typical data center prepared by

The graphic at right may look kind of cool, but it’s anything but. It’s actually a simulation of the heat distribution of a typical data center prepared by