This is a draft of chapter 10 of Social Marketing to the Business Customer by Paul Gillin and Eric Schwartzman. This chapter focuses on how to calculate ROI of social media and Internet marketing programs in general. I’m particularly interested in your feedback on this chapter because it presents some new ideas I’ve been playing with about how to calculate the ROI of almost anything. My biggest concern is that these ideas are overly simplistic. They do assume that a company has a rich set of historical data to work with, which is often not the case.

Please ignore the typos and grammar flaws that invariably appear at this stage.

We’ve told you about a few companies that have achieved a notable return on investment (ROI) from their social marketing initiatives. They include Indium Corp., whose blog-driven search strategy yielded a six-fold increase in leads in just one quarter, and Clickable, whose Gurus drove a 400% one-year growth in billings.

These numbers are impressive, but in our experience, they’re more the exception than the rule. In conversations with hundreds of marketers over the last few years, we’ve observed that few of them closely track the ROI of their social marketing programs. In fact, many of the most successful marketers aren’t that concerned with ROI at all. Rather, they invest in social marketing because they believe that the benefits – customer engagement, market awareness, continuous feedback and professional development – are good for

any company, regardless of the financial impact. They measure like crazy, but they rarely translate the benefits of engagement into hard dollar figures.

Most of these early adopters work for companies with adaptive, change-oriented management. That’s good if you can get it, but the reality is that most top executives are still wary about social marketing. ROI is typically the number one or two most cited concern we hear from the people who work for these companies.

We’re conflicted about the whole ROI debate. On the one hand, we believe that businesses should make decisions based on sound reasoning rather than vague promises or impulse. ROI analysis enforces rigor that leads to better decisions. On the other hand, we believe ROI objections are often used to avoid decisions that executives don’t want to make for other reasons, such as fear of losing control. Few people want to admit that they’re afraid, so they fall back on convenient stalling tactics, of which ROI is a primary one.

The reality is that businesses make decisions without applying hard ROI criteria all the time. Much of the money that B2B marketers have poured into direct mail campaigns, trade show exhibitions and trade print advertising for the last 50 years has questionable returns. The only reason we make these investments is that these practices are established and businesses are accustomed to them. “ROI calculations don’t work well for social media and they don’t work well for marketing in general,” says Benjamin Ellis, a UK-based serial entrepreneur who now specializes in social marketing.

What’s the return on landscaping, an expensive conference room table or free bagels on Fridays? It may be possible to calculate a payback through extensive customer perception or employee satisfaction analysis, but why bother? We know these investments make people feel better. If your employees feel better, they do a better job and your customers feel better.

EMC Corp. has been known to charter jets to fly technicians across country in the middle of the night to take care of a customer whose computers are down. Do you suppose the storage giant conducts an ROI analysis before making that decision? Of course not. EMC is a premium-priced provider whose philosophy is to always go the extra mile to take care of the customer. In the aggregate, the company may be able to justify its practices in the form of higher customer satisfaction and repeat sales, but we doubt the support manager who charters the midnight express is required to justify the added expense in advance.

That said, we understand the ROI justification is a hurdle many marketers must clear to get their social programs off the ground. We believe that many social marketing programs can be justified, but the process requires discipline and careful documentation. After all, the Internet is the most measurable medium ever invented. If you can isolate variables, establish correlations and apply a little creativity, it’s remarkable what you can do. In this chapter, we’ll suggest some approaches.

Defining ROI

A lot of marketers would probably like to be in Susan Popper’s shoes. The VP of marketing communications at SAP was recently asked by B-to-B magazine how she is measuring ROI on marketing efforts. Her response: “When [our target audiences comes] to our site, they watch the videos and they are engaging with the content on the site. Our impression-to-visit ratio (as measured by click-through rates) doubled this year versus last year.” That’s an impressive result, but it isn’t a return. In order to compute return, you need to think in financial terms.

According to Wikipedia, ROI is “the ratio of money gained or lost (whether realized or unrealized) on an investment relative to the amount of money invested.” There are two important variables in this equation: Return and Investment. There’s also a third vital term: Money.

Return is payoff as measured in revenue generated or costs avoided. There are other ways to measure return (for example, improvement in customer satisfaction scores), but unless those outputs can be measured financially, they really don’t qualify as considerations in ROI. We believe many of these intangibles actually can be translated into financial terms, and we’ll cover that later in this chapter.

But for now, let’s look at a couple of basic examples. A simple one is an ROI analysis of the impact of hiring a new sales representative. Let’s say the new rep carries a fully loaded cost of $100,000 and delivers $2 million in incremental annual sales revenue at a 10% net profit. In that case, the first-year ROI of hiring the salesperson is 100%, expressed as profit divided by investment:

|

Cost of sales rep

|

$100,000

|

|

Revenue generated by rep

|

$2,000,000

|

|

Profit margin

|

10%

|

|

Net profit

|

$200,000

|

|

ROI ((net profit – cost)/cost)

|

100%

|

We can apply the same type of analysis to cost avoidance. That’s what Pitney Bowes did when a 2007 Postal Service rate increase prompted 430,000 calls from customers. The mailing service provider launched an online forum to deflect some of the most common questions and tracked 40,000 visits in six weeks. Pitney Bowes was able to correlate savings in call center costs and estimate that the forum more than paid for its first-year costs in just a short time.

Let’s say we implement a customer self-service portal as a way to reduce support costs. We assume that the portal will require half of one full-time equivalent (FTE) employee to administer, that the fully loaded cost of that employee is $70,000 and that the portal will enable the company to eliminate one support position at a fully loaded cost of $70,000. Let’s further assume that efficiencies will enable us to reduce administrative support costs to one-quarter of an FTE the second year and 10% the third year. At the same time, the value generated by the community will enable us to cut an additional one-half customer support position each year.

Here’s what the analysis would look like:

|

Year

|

Item

|

Annual

|

Cumulative

|

|

1

|

Administrative costs

|

$ 35,000

|

$ 35,000

|

|

|

Savings

|

$ 70,000

|

$ 70,000

|

|

|

ROI

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

2

|

Administrative costs

|

$ 17,500

|

$ 52,500

|

|

|

Savings

|

$ 105,000

|

$ 175,000

|

|

|

ROI

|

500%

|

233%

|

|

3

|

Administrative costs

|

$ 7,000

|

$ 59,500

|

|

|

Savings

|

$ 140,000

|

$ 315,000

|

|

|

ROI

|

1900%

|

429%

|

The portal looks like a good investment, yielding a positive first-year ROI and blowout value in the third year. The cumulative value is also very strong. Even if our annual savings estimates are off by 50%, we’d still get nearly a 10-fold return on operating costs in year three.

These are two simple examples, but they both require confident forecasting based upon accurate historical data. For many companies, that’s far from simple. In the case of the sales rep, we must be able to predict with reasonable certainty that the person can generate $2 million in incremental business in year one. There are a lot of factors underlying that assumption. For example, we assume predictable growth in the overall market and in our growth rate relative to the market. We must be confident that there is $2 million in new business out there to find. In niche B2B markets with a small number of potential customers, that assumption may be optimistic. And then there are unforeseen circumstances: The bankruptcy of a major competitor could move that revenue goal higher, while the emergence of new competition might force us to trim our forecasts.

There are also nuances of calculating net present value, inflation, opportunity cost, return on capital and other fine points of finance that we won’t try to cover here for the sake of simplicity. ROI calculations are rarely a precise science to begin with.

History and Correlation

Good ROI analysis almost always requires accurate historical information, which few companies have, in our experience. Capturing and analyzing historical data requires time and discipline. It’s easy to cast aside analytical tasks when everyone is focused on generating revenue. However, you can’t forecast the future without understanding the past. Historical data also sets a baseline for measuring change. That change can then be measured and compared to actions that may have caused it. If you can correlate action to impact, then you can calculate ROI.

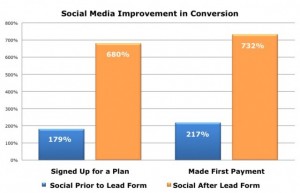

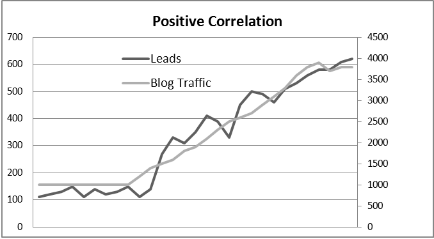

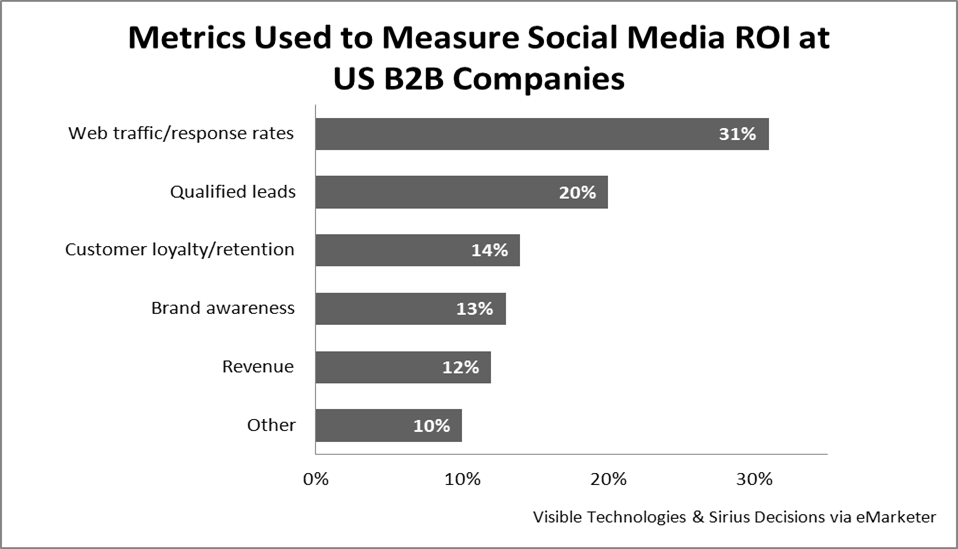

In the example below, lead activity appears to correlate positively with traffic to a company blog. The positive correlation is indicated by the change from baseline, which appears to correspond with the upward movement in blog traffic. Even then, a definitive correlation can’t be established until other factors are eliminated from consideration, such as a promotion or a new advertising campaign.

Identifying correlations can be a time-consuming process, requiring new variables to be introduced independently of each other so that change can be isolated. However, you don’t necessarily have to test only one variable at a time. With split testing, you can try two different experiments, each targeting a different segment of your customer base.

Identifying correlations can be a time-consuming process, requiring new variables to be introduced independently of each other so that change can be isolated. However, you don’t necessarily have to test only one variable at a time. With split testing, you can try two different experiments, each targeting a different segment of your customer base.

Suppose you license e-mail marketing services to customers on a subscription basis. For the last three years, your renewal rate has been about 40% annually, so you can reasonably expect that trend to continue. This gives you a baseline from which to test new tactics.

You’re going to try out two new incentives this year to increase renewal rates. One provides a 10% discount on the annual fee to each customer that renews more than one month ahead of deadline. The other provides access to six customer-only educational webcasts during next 12 months for all customers who renew, regardless of timing. Each eligible customer gets one incentive or the other. This should give you a sound indication of ROI because you can compare your results to historical data.

It turns out that both programs are equally successful in boosting renewal rates, but the webcast promotion has a better ROI. That’s because 40% of the renewing customers who were offered the discount renewed before the one-month deadline, which incurred a higher discount obligation. Not only was the webcast promotion more cost-effective, but it carried a predictable cost of about $1,500 per webcast, compared to the variable cost of the discount. The webcast is probably the smarter incentive to offer.

|

|

Historic

|

With 10% discount

|

With webcast

|

|

Expiring customers

|

100

|

100

|

100

|

|

Average subscription cost

|

$ 5,000

|

$ 5,000

|

$ 5,000

|

|

Renewal rate

|

40%

|

60%

|

60%

|

|

Profit margin

|

20%

|

20%

|

20%

|

|

Profit from renewing customers

|

$ 40,000

|

$ 60,000

|

$ 60,000

|

|

Incremental profit from incentive

|

N/A

|

$ 20,000

|

$ 20,000

|

|

Cost of incentive

|

N/A

|

$ 12,000

|

$ 9,000

|

|

ROI

|

N/A

|

67%

|

122%

|

This example presupposes that the company has good data about past renewals, but many companies lack the systems to capture complete data in the first place. A good CRM system is essential. Many excellent solutions are now available on a software-as-a-service basis today, including Salesforce.com, RightNow Technologies and NetSuite. You can find a complete directory at Saas-showplace.com. But choosing the tool isn’t nearly as important as knowing how to put it to work.

Effective CRM requires discipline to capture every customer contact from initial website visit through sale and continuing with ongoing support. That means involving more than just the sales force in the process. To calculate the ROI on social marketing, you need to understand every dimension of the customer relationship, beginning with the action that creates the first contact. It’s not enough to begin tracking when the lead is generated. Marketing should have the systems in place to identify the action that created the lead, whether that’s a search query, e-mail link, customer referral or some other event. Most CRM systems are good at tracking customer activity after leads come in. The difficult job for marketing is figuring out the sequence of events that brought them there.

We can’t emphasize this enough: Being able to predict the future means knowing a lot about the past. If you can’t establish effective baseline expectations, then your forecasts are little more than educated guesses. In order to do ROI right, you need to track every customer contact, not just interactions with the sales force.

Metrics

Web analytics today deliver unprecedented insight about online interactions. The basic features of the free Google Analytics service match the capabilities of products that cost thousands of dollars just a few years ago. Premium services like Webtrends build in sophisticated behavioral and sentiment analysis and can track offsite activity such as a prospect’s comments on Twitter or use of a mobile application. They can even trigger customized e-mails or tweets when a person’s behavior matches certain predefined patterns.

With all this rich data now available, it’s remarkable how many marketers still use the basic metrics of traffic and unique visitors to measure success. We’re not big fans of these measurements; it’s easy to generate spikes of valueless traffic by posting celebrity photos or top-10 lists, for example. In Chapter XX, we listed some common metrics you can use and how they relate to different business goals. We think richer measures such as referring keywords, top content, bounce rate, average time spent on site, pages-per-visit and content analysis yield more actionable insight that will only get better.

The best way to select relevant metrics is to work backwards. Start with sales trends, match them to Web activity and look for the metrics that correlate most closely. Those are the metrics that are most meaningful to you. For example, if an increase in session time spent on site appears to correlate with registrations for a webcast, then that indicates that webcasts resonate with the audience.

You also shouldn’t confine metrics to those which can be measured online. One of the most popular indications of customer satisfaction is the Net Promoter Score (NPS), introduced in 2003 by Fred Reichheld of Bain & Co. Obtaining an NPS requires asking customers a single question on a 0-to-10 rating scale: “How likely is it that you would recommend our company to a friend or colleague?” This simple tactic has been adopted by big B2B companies like General Electric and American Express as a key performance indicator.

You can also choose to monitor classic metrics that have nothing to do with the Internet. These include press mentions, speaking invitations and performance on customer satisfaction surveys. Metrics also vary by objective. For example, the success of a blog set up to generate leads may be measured by inquiries, time spent on site and to repeat visitors, while one targeted at search optimization may be evaluated based on keyword rankings and inbound links.

For ROI purposes, though, the choice of metrics is less important than your ability to correlate behavior to results. In other words, if certain page views are more valuable than others, then an increase in traffic and session time could be a good starting metric for evaluating ROI. Just be aware that they are imperfect indicators of visitor engagement.

One thing you absolutely need to know, however, is how people reach your site. Unique URLs are a way to measure that. We’re astonished at how many e-mails we still get from brand-name companies that don’t make use of this simple tactic, which enables a marketer to specify a web address that is unique to the e-mail, tweet, wall post or any other message. Unique URLs use a simple server redirect function to identify the source of an incoming click. They look like this: https://mycompany.23.com/public/?q=ulink&fn=Link&ssid=5155. Everything after the word “public/” is a unique code that tells where the visitor came from.

Unique URLs enable your analytics software to track inbound traffic from each source separately so you can determine the ROI of each channel. Without unique URLs, visits are simply classified as “direct traffic,” meaning that the source could be a forwarded e-mail, bookmark or an address typed into the browser.

A simple example of how you might use this information is to measure traffic to a landing page and analyze the number of visitors who fill out a registration form according to the referring source. This would show you, for example, that registration rates are twice as high from a newsletter as from a tweet. The value of those registrants divided by the cost of the newsletter is an ROI metric. Unique URLs are also valuable to split testing; you can try out two different invitation messages in the same email and use a different URL for each to measure response to each message.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

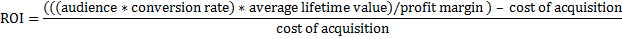

Let’s apply all the factors we’ve described above to two B2B social marketing scenarios. First, we’ll compare the ROI of webcasts to white papers. Start with historical data. What is the conversion rate of webcast viewers versus people who download a white paper? What is the lifetime value of an average customer? Compare the outputs and divide by costs to assess ROI:

Let’s assume the following:

· The average lifetime value of a customer is $50,000 at a 10% profit margin.

· The average cost of delivering a webcast to 100 registered viewers is $3,000; viewers convert at a 2% rate;

· The average cost of delivering a white paper to 500 registrants is $10,000; registrants convert at a 1% rate.

Our ROI analysis looks like this:

|

|

Webcast

|

White paper

|

|

Audience size

|

100

|

500

|

|

Conversion rate

|

2%

|

1%

|

|

Lifetime profitability

|

$ 10,000

|

$ 25,000

|

|

Cost of acquisition

|

$ 3,000

|

$ 10,000

|

|

ROI

|

233%

|

150%

|

The webcast ROI is superior, but not by much. Armed with this data, we might choose to promote the webcast more aggressively to leverage its stronger ROI. However, another option would be to focus on improving the white paper’s conversion rate. In fact, doubling the rate would drive ROI to 400%, making this a potentially higher return action.

Let’s look at one more example in which we use a blog for lead generation. We know that performance will be slow during the first few quarters until search engine traffic kicks in. Based upon the experience of others, we believe that lead growth will improve steadily as traffic builds. We expect to be at 50 leads per month by the end of the first year and 160 per month by the end of the second. Our historical data tells us that a lead is worth $100. We further estimate our editorial costs at $2,000 per quarter during the first year, doubling to $4,000 during the second. Here’s our analysis of quarterly and cumulative ROI.

|

|

Leads

|

Lead value

|

Cost

|

Quarterly ROI

|

Cumulative ROI

|

|

Y1Q1

|

10

|

$ 1,000

|

$ 2,000

|

-50%

|

-50%

|

|

Y1Q2

|

25

|

$ 2,500

|

$ 2,000

|

25%

|

-13%

|

|

Y1Q3

|

35

|

$ 3,500

|

$ 2,000

|

75%

|

17%

|

|

Y1Q4

|

50

|

$ 5,000

|

$ 2,000

|

150%

|

50%

|

|

Y2Q1

|

75

|

$ 7,500

|

$ 4,000

|

88%

|

63%

|

|

Y2Q2

|

100

|

$ 10,000

|

$ 4,000

|

150%

|

84%

|

|

Y2Q3

|

130

|

$ 13,000

|

$ 4,000

|

225%

|

113%

|

|

Y2Q4

|

160

|

$ 16,000

|

$ 4,000

|

300%

|

144%

|

This gives us a firm foundation to make the case for investing in the blog. If leads aren’t coming in as quickly as we had estimated, we can adjust costs downward to improve ROI by setting up content-sharing arrangements.

Measuring Intangibles

The trickiest aspect of ROI analysis is accounting for intangibles. These include factors like customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, brand reputation and market influence. Many social marketing projects are justified for these reasons but the outputs are never measured, either because it’s not worth the effort or because the measurements aren’t in place.

In fact, all of these outputs can be measured and have been for years using some of the following tests:

|

Value

|

Measurement

|

|

Customer satisfaction

|

Customer surveys; renewal rates; referrals; incremental business; testimonials; Net Promoter Score

|

|

Customer loyalty

|

Renewal rates; incremental business, response rates, event attendance; testimonials; Net Promoter Score

|

|

Customer engagement

|

Newsletter subscriptions; online community activity; response rates; event attendance; testimonials; feedback volume

|

|

Reputation

|

Market share research; awareness research; media citations; analyst research

|

|

Market influence

|

Market share research; lift studies; media/social media citations; speaking invitations; analyst research

|

|

Leadership

|

Attitudinal research; growth rate; media citations; copycat competitors

|

However, research statistics aren’t sufficient. You have to find a way to translate these measurements into dollars and cents. That’s where creativity comes in handy. Many of the metrics on the right can be mapped to business outcomes, but only if historical data is available to correlate to those changes.

For example, you can calculate the business value of customer loyalty by comparing the revenue derived from customers at different longevity levels, such as five-plus years, three to five years and less than three years. Then look at the support and sales costs allocated to these same customers. You’ll probably find that long-term customers are cheaper to support and have lower sales costs than newer customers. Comparing the ratio of revenue to expense for each longevity segment should give you an idea of where to invest.

What is the business value of reputation? There’s a lot of research to indicate that B2B customers weigh this factor heavily when making buying decisions. A simple telephone survey can identify who these customers are. You can then see where they rank in order of value to your business. If they are near the top (and we believe they will be) then that is compelling evidence that investment in reputation pays off. You can compare the average profitability of these customers versus those who don’t value reputation as highly and see which has more investment upside.

You can even quantify, to some degree, factors that are almost impossible to measure. For example, suppose that a publicity campaign results in five million impressions in mainstream media. By conducting pre- and post-campaign “lift” studies, you can measure changes in awareness. Then drag out the record books to compare previous increases in awareness to corresponding changes in the business, such as lead quality and conversion times. You can quantify the value of those outputs to calculate ROI.

Once again, these analyses require accurate historical data. If you can’t segment your customers according to criteria like these, the justification process is far more difficult. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible, though. Analyst estimates, industry averages and ratios derived from analyzing your competitors and those in other industries may yield similar insights.

How does this all relate to social marketing? We believe it’s critical. The ROI objection is the roadblock you’re most likely to encounter in selling a social marketing initiative. You need to speak the language of your inquisitors. Social marketing has also introduced new cost variables into the business. For example, press tours used to be a standard tactic for increasing market awareness, but today a blog may do the same thing at a much lower cost. In order to understand the true value of these new tools, you need to have a baseline for comparing them to past practices. Get your Excel skills in order, because you’re going to have some explaining to do.

Sidebar – Valuing Twitter Followers

When marketers get up on stage to describe their social marketing successes these days, they invariably refer to follower and fan totals. On Twitter, follower counts have become a sort of merit badge, despite the fact that anyone can quickly run up that number by simply auto-following everyone who follows them. There are even paid services that inflate follower totals.

What is the true value of a Twitter follower? There is no industry standard to calculate that number, but if you have the right metrics in place, you can do that for your own organization. Here’s how:

Look at the total number of clicks to your site from Twitter in any given month and divide that by the number of tweets you posted. This gives you the average visits per tweet. Once you have this number in hand, you can look at the behavior of visitors who arrive from Twitter and compare it to those who find you from other sources. Look at page views per visit, time spent on site and visitor paths to identify what percentage of Twitter visitors become leads or customers. Using your standard qualifying metrics, you should be able to determine the average value of a Twitter visitor.

For example, if 1,000 visitors arrived from Twitter in a given month as a result of 20 tweets, that yields an average of 50 visits per tweet. If you know that 5% of Twitter visitors register for a download or newsletter, and that the value of an average registrant is $50, then you can calculate that Twitter delivers $2,500 in business value, or an average of $125/tweet. If you have 5,000 followers, then you can also calculate that an average follower is worth 2.5 cents.

This formula is overly simplistic, of course. Not all Twitter followers are created equal. If you want to dive deeper into the mechanics of influence, services like TweetReach.com and Twinfluence.com can calculate the total reach of your followers or tweets according to so-called “second-order followers,” or those who follow the people who follow you. These metrics can also be used to estimate the value of retweets by certain popular members.

This same approach may also be applied to finding the value of Facebook fans, LinkedIn connections, SlideShare followers and the like.

End sidebar

Have you checked out LinkedIn lately? If you thought the world’s largest professional network was little more than a place to post your resume, you owe yourself another visit. LinkedIn is set to eclipse the 100 million member mark sometime this spring, and it is quickly becoming the social network of choice for B2B professionals.

Have you checked out LinkedIn lately? If you thought the world’s largest professional network was little more than a place to post your resume, you owe yourself another visit. LinkedIn is set to eclipse the 100 million member mark sometime this spring, and it is quickly becoming the social network of choice for B2B professionals. Ask and Answer. Many of the questions posed within groups and in LinkedIn’s busy Answers section concern requests for expertise. You can subscribe to questions in your domain using an RSS reader, which ensures that you will never miss one that matters to you. If the technical gurus in your organization are intimidated by the prospect of blogging, urge them to instead answer five questions per week. As they grow their profile in the community, people will start seeking them out for business. That’s the reason Vico Software expects its sales reps to become active in construction-related groups in each of their territories. They’ll find out first about new construction opportunities in the forums.

Ask and Answer. Many of the questions posed within groups and in LinkedIn’s busy Answers section concern requests for expertise. You can subscribe to questions in your domain using an RSS reader, which ensures that you will never miss one that matters to you. If the technical gurus in your organization are intimidated by the prospect of blogging, urge them to instead answer five questions per week. As they grow their profile in the community, people will start seeking them out for business. That’s the reason Vico Software expects its sales reps to become active in construction-related groups in each of their territories. They’ll find out first about new construction opportunities in the forums.

That industry is debt relief, a field that many people associate with fast talking pitchmen on late-night infomercials. But there’s nothing underhanded about CareOne, a nine-year-old company with 700 employees and a philosophy that “There’s no reason to be ashamed of being in debt,” according to Social Media Director

That industry is debt relief, a field that many people associate with fast talking pitchmen on late-night infomercials. But there’s nothing underhanded about CareOne, a nine-year-old company with 700 employees and a philosophy that “There’s no reason to be ashamed of being in debt,” according to Social Media Director