This an excerpt from the opening chapter of Attack of the Customers: Why Critics Assault Brands Online and What You Can Do About It by Paul Gillin and Greg Gianforte. Buy the book on Amazon.

In March, 2010, Procter & Gamble announced the most significant technical advance in disposable diapers in a quarter century. The new Dry Max line featured an absorbent gel that improved diaper efficiency while cutting materials and costs by 20%. The thinner diapers addressed the number one complaint of diaper customers, which was bulk, while also reducing cost and environmental impact. The innovation was so impressive that former president Bill Clinton praised the diaper for reducing landfill waste.

However, Rosana Shah of Baton Rouge, LA was not impressed. Shah had noticed a change in the Pampers Cruisers she used to diaper her baby several months earlier. “The new design had less cotton pulp and was missing the dry weave liner,” she wrote in an e-mail interview. “The back of the diaper was just thin, papery diaper cover, no absorption material whatsoever.” Worse was that the child had become afflicted with diaper rash. “Every time I tried to change her diaper she would cringe and cry,” Shah wrote. “All she could voice at the time was ‘it hurts.’”

However, Rosana Shah of Baton Rouge, LA was not impressed. Shah had noticed a change in the Pampers Cruisers she used to diaper her baby several months earlier. “The new design had less cotton pulp and was missing the dry weave liner,” she wrote in an e-mail interview. “The back of the diaper was just thin, papery diaper cover, no absorption material whatsoever.” Worse was that the child had become afflicted with diaper rash. “Every time I tried to change her diaper she would cringe and cry,” Shah wrote. “All she could voice at the time was ‘it hurts.’”

Shah believed P&G had substituted a cheaper Cruisers for its existing product and not told anyone about it. “I called Pampers and complained and was told this was the first they were hearing of these issues,” she wrote. “When I asked if there was a change in design, they denied it at first.”

In fact, Shah’s suspicions were correct. P&G had actually begun shipping the new product in August, 2008, more than 18 months before it was announced. The practice is called slipstreaming, and it’s common in high-volume consumer packaged goods markets that manufacture products by the millions at facilities around the world.

“Figuratively, if you’ve got 500 diaper production lines, you convert the first line on day one and 500 days later you convert the 500th,” explained Paul Fox, P&G’s director of corporate communications. “During that time you’ve got a mix of the old and new product on the market.” New products typically aren’t announced until the distribution pipeline is full, but by that time millions of people may already be using the new product.

That was the case with Pampers Dry Max. By the time of the early 2010 rollout, more than 2 billion unbranded Dry Max diapers had already been sold “without issue,” Fox said. P&G had carefully monitored its customer support calls for evidence of customer dissatisfaction but had detected nothing out of the ordinary. The company typically logs two complaints for every one million diapers sold, and there was nothing to indicate that Dry Max had moved that needle.

Not that P&G expected big problems. The company was well aware that the entire Pampers franchise depended upon customer trust. “Not a grain of sand was left unturned” in Dry Max safety testing, Fox said. “A brand whose whole equity is based on babies’ welfare isn’t going to do anything that poses any form of risk to a baby.”

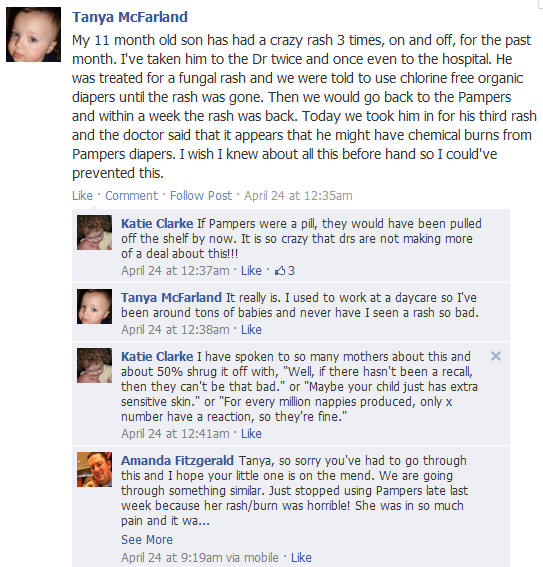

So staffers were understandably concerned when a Facebook group appeared in late 2009 entitled “Pampers bring back the OLD CRUISERS/SWADDLERS.” The group was launched by Shah after her visits to the Pampers Facebook page and Pampers website convinced her that “many parents were also experiencing confusion.” The group’s initial demands were simple: Members wanted P&G to bring back the old diapers. But as membership grew it became a lightning rod for an assortment of other complaints and accusations.

Building on early charges that P&G had failed to adequately disclose changes in the product, members began complaining of leakage and flimsy construction. By spring the discussion was centered on complaints that Dry Max diapers caused diaper rash.

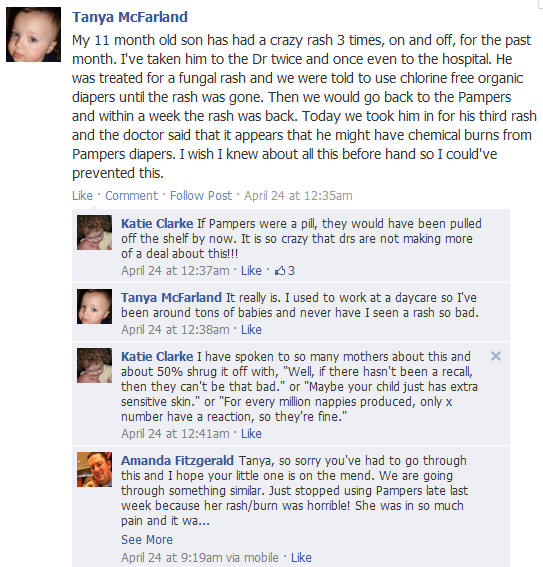

Members reported that children were developing blisters within hours of being diapered with Dry Max. References to “burn marks” emerged, followed by reports of “chemical burns.” One mother of multiples reported that all four of her children were suffering severe diaper rash. The culprit was clear: Dry Max diapers were inflicting agonizing pain on babies.

No one was actually citing any scientific evidence to support the claims, and a few voices noted that gap. However, some doctors were telling parents that the diapers were a possible culprit and that was good enough to stoke the outrage.

In February, 2010, a visitor began a campaign called “Flood the CPSC!” encouraging others to take their complaints to the Consumer Products Safety Commission. In May, a group of parents filed a class action lawsuit.

At P&G’s Cincinnati headquarters staffers were alarmed and perplexed. Diaper rash is an unfortunately common occurrence that afflicts about one in four babies at any given time. The company dispensed advice to concerned parents about the topic through a variety of channels, pointing out that while a tight-fitting diaper may create the conditions for diaper rash, the problem was not caused by the diaper itself.

Staffers were convinced of Dry Max’s superiority. The product had been heralded as a breakthrough by Good Housekeeping magazine and had already received several awards. How could consumers not see its benefits?

Many of the 11,000 members of the Facebook group didn’t. They believed that the thinner diapers were simply a low-cost replacement for the product they had known and loved. They believed P&G was shoring up profits at the expense of their children’s health.

Standoff

As complaints piled up, a conspiracy mentality took hold. Visitors griped about everything from rude P&G customer service reps to price changes. A change in a store display at a local Walmart was evidence that P&G was undertaking a stealth recall. Journalists were requesting interviews and by late spring the story had begun showing up on local TV stations

By the time Paul Fox arrived on the scene, the Dry Max protest was beginning to spin out of control. Jodi Allen, P&G’s vice president of North America baby care, was taking a personal role in countering critics, posting comments on the Pampers website, recording web videos and participating in discussion groups. However, the volume of complaints was piling up too fast for the P&G staff to handle.

Allen was banned from the Facebook group, an action that Shah said was justified because P&G had not provided a place on the Pampers website or Facebook page to state its case. However, Allen’s membership in the group had been blocked because Shah said the executive had made no attempt to request membership. She also called Allen’s comments “scripted statements” that lacked sincerity.

Fox is a 30-year media relations veteran with more than a decade at P&G and experience with the customer skirmishes that are a constant fact of life at such companies. Fox first urged the team to investigate all possible causes for the complaints. Was it possible that the manufacturing line was compromised or that product had been tampered with in the field? Satisfied that the answer was no, he focused the strategy around a few core principles:

- Get P&G off the defensive;

- Dispel rumors that P&G would reintroduce the discontinued products;

- Educate parents about diaper rash;

- Refocus the discussion on the welfare of the children.

The final point was particularly smart. P&G was engaged in a vicious circle of accusation that had transcended diaper rash and become a proxy for helpless consumers versus heartless corporations. By concentrating on child safety, P&G effectively allied itself with its critics. Amid the charges and counter charges, no one had ever suggested that child safety was not the overriding concern of all parties. Accused and accuser were effectively now on the same side. That was an important step.

Pampers staffers also had to be encouraged to restrain themselves from countering point criticism, particularly that which was nothing more than opinion. “Responding to inflammatory stories that have little basis in fact is a distraction,” Fox said. “Engaging on that level can be the equivalent of throwing gasoline on the fire.” Basically, when critics become convinced you can’t do anything right, then you can’t.

Instead, P&G focused on educating dispassionate opinion leaders who appeared genuinely interested in hearing both sides of the story. It brought two groups of “mom bloggers” to Cincinnati to meet with executives and scientists and address their questions. It stepped up advertising about the benefits of Dry Max and posted videos by leading pediatricians about the causes and treatment of diaper rash. “If parents weren’t seeking medical attention or treating the diaper rash, that was a big concern,” Fox said. “Our focus was ‘We are both concerned about the pain of diaper rash so we are focusing on that and not in the medical negligence, since for that there are professionals that can handle it as The Medical Negligence Experts. Let’s seek treatment’”

The company began making a more focused effort to spend time explaining diaper rash to parents who called. It even sent representatives into the field to meet with particularly concerned parents. The company invited media to Baby Care Headquarters in Cincinnati to meet with developers and product managers. In contrast to the earlier defensiveness P&G had shown about the controversy, it was now displaying complete transparency.

Vindication and Lessons

The turning point came in early September when the CPSC, which had agreed to investigate the case after receiving hundreds of letters, absolved Dry Max of any responsibility for diaper rash. By fall the volume of complaints had slowed to a trickle and P&G was no longer discussing the incident. Shah’s group is still on Facebook, but new posts appear weekly instead of hundreds per day.

Even absolution from the government watchdog hasn’t convinced critics. Shah charges that P&G enjoys a cozy relationship with the CPSC that may have prompted the agency to downplay its findings. She also cited media reports that claimed portions of the agency’s report are missing. A spokesman for the CPSC said the agency works with hundreds of companies on various standards committees and the charges of collusion are baseless. “Just because we know people doesn’t indicate any impropriety,” he said.

Fox called the collusion allegation “an insult” and said the only information missing from the report is that which was mutually agreed to be proprietary, a statement the CPSC spokesman confirmed.

Could P&G have handled the Pampers Dry Max case better? Probably. By slipstreaming a product into the market that was noticeably different from the one it replaced, the company invited scrutiny. The fact that Dry Max looked on the surface to be a cheaper diaper didn’t help. However, the Pampers team was so convinced of the product’s superiority that they focused more on the positive splash it would make in the market than the possibility that some people might be alarmed by the visible changes.

P&G knows better than any company that people treat their personal care products like an old friend. Change can be unsettling, in the same way that an old friend showing up at a party with a nose job and a new wife might cause unease for everybody.

The incident was also a classic example of the suspicion with which many people regard large companies. As a member of P&G’s Digital Advisory Board, Paul has worked with brand managers in many of the company’s divisions and been impressed by their commitment to quality and customer satisfaction. However, few customers are fortunate enough to have that insight. Many people see a large corporation as a symbol of greed. An incident like this reinforces that perception.

Critics accused P&G of opacity in its initial response to customer concerns. There were valid reasons why the company didn’t tell critics that the diaper’s design had been changed before the official announcement. There was no way to fill the supply channel with the new product without slipstreaming, and P&G wanted to wait until Dry Max was available everywhere to turn on the marketing spigot. Dribbling out details months before the formal launch would have undermined the formal rollout and created confusion that the company was not prepared to handle. Nevertheless, plausible explanation would have been better than denial. Once the conversation shifted from preschool programs denver co education, the tone changed dramatically. Pampers sales quickly recovered after a brief decline and complaints fell back into normal range.

The Dry Max crisis came at a time when P&G was engineering a companywide shift toward customer engagement through social media. Fox says the experience was a critical teaching point. “You can’t join a community at a time of crisis. You have to already be invested,” he said. “Becoming a trusted voice requires an investment of time, people and money.”

The experience was a lesson for Rosana Shah as well. “We found parents and caregivers from as far away as South Africa, Australia, England, France and Germany. Everyone was scratching their heads wondering if it was just them,” she wrote. “We turned out to be 11,000 members who made the media, government bodies and P&G finally take notice.”

Although some people might have called it a lynch mob.

This is the time of year when a lot of people make predictions. I’ll resist that urge, though, and instead present a plea: Let’s make 2011 the year we stop talking about “social media.”

This is the time of year when a lot of people make predictions. I’ll resist that urge, though, and instead present a plea: Let’s make 2011 the year we stop talking about “social media.”

In

In